Link color codes:

English|Scandinavian

Britannica

Wikipedia

Project Gutenberg

Questia

The Teaching Company

FindArticles

News:

The Economist

Depesjer

Sploid

Music chart:

From the archives:

Remember, remember 11 September; Murderous monsters in flight; Reject their dark game; And let Liberty's flame; Burn prouder and ever more bright

- Geoffrey Barto

"Bjørn Stærks hyklerske dobbeltmoral er til å spy av. Under det syltynne fernisset av redelighet sitter han klar med en vulkan av diagnoser han kan klistre på annerledes tenkende mennesker når han etter beste evne har spilt sine kort. Jeg tror han har forregnet seg. Det blir ikke noe hyggelig under sharia selv om han har slikket de nye herskernes støvlesnuter."

- Anonymous

2005: 12 | 11 | 10 | 09 | 08 | 07 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 02 | 01

2004: 12 | 11 | 10 | 09 | 08 | 07 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 02 | 01

2003: 12 | 11 | 10 | 09 | 08 | 07 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 02 | 01

2002: 12 |

11 |

10 |

09 |

08 |

06 |

05 |

04 |

03 |

02 |

01

2001: 12 |

11 |

10 |

09

April's Fool: 2002 |

2003 | 2004

| Sunday October 09, 2005 by Bjørn Stærk |

All new conspiracy theories take us by surprise. We walk around safe in our beliefs, safe that they're sane beliefs, shared by all the sane people of the world. And then somebody starts boldly hacking away at their pillars. See, there's an alternative view, shared by other sane people, brave and few and righteous, and they're being persecuted by the establishment, and there are so many holes in the mainstream theory it's not even funny.

"What?! I never heard about that.. I don't believe you. Everybody knows .."

"I know, I used to be just like you. But then I did some research, and the evidence is just overwhelming. Read this book, I haven't met anyone who can refute it. Read it, make up your own mind."

After surprise there's denial. Stubborn, defensive denial. This leaves us vulnerable. Rational people know they're not supposed to react to new ideas with stubborn denial, and they're ashamed of it. After that, one of three things happen:

- You read some recommended literature, which poses questions you can't answer, and has a tone of rationality and honesty you find convincing. You then drop your old belief, and embrace the new. The world takes on a different appearance.

- You just plain refuse to listen, following the reliable rule of thumb that radical minority views are never worth listening to. You reply with an insult, a smirk, or an appeal to authority, and walk away. This is a bit cowardly, but it's a safe strategy that pays off in the long run, like saving money in the bank instead of day trading on the stock market. If you tend to choose this option, you're a pillar of society, a force of caution and inertia. Good for you!

- You take the new ideas seriously enough to investigate their basis and counter them with skepticism and arguments. You try to learn whatever you feel you need to know to judge the issue fairly. You want to prove them wrong, but you also don't want to win by cheating. Eventually, either they convince you that you're wrong, (see outcome nr 1), or you give up trying to convince them, but at least you leave the encounter knowing more about what you believe in and why. Like with the inoculation methods people used before the smallpox vaccine was invented, there's risk and effort involved taking this approach, but if you succeed it'll make you immune to that particular infection.

I've tried all these approaches. You don't meet at lot of conspiracy theories in the mainstream media, but you do meet many of them on discussion boards, on Usenet and in blogs. This is because there are more ideas floating around there. So there's more evolutionary pressure, which favors the predators. Anyone who spends time online will be exposed to a few.

I've tried conversion, denial and argument. Converted to Chomskyism once, spent a while in ZMag-land. Argued for months with a neo-Nazi Holocaust denier. Eventually I think I developed a kind of general immunity. There's a smell to conspiracy theories, a smell you can detect long before their followers bring out the black helicopters and UFO abductions. It's there in the way they talk and think, you just have to pay attention.

And here's what's funny: Once you've learned to detect it, that smell of conspiracy is often there even when there is no conspiracy, even when there are no black helicopters, and the space moose army isn't about to invade us. It's everywhere, in common beliefs that surround us, beliefs that aren't wacky or evil, but use a similar conspiracy-like approach all the same. Just like non-lethal viruses use the same tricks as lethal viruses to spread themselves, the tricks real conspiracy theories use aren't exclusive to them. They're too effective for other bad ideas not to adopt.

Before the internet, these tricks were less of a threat to us, because the same gatekeeping that have made traditional media so stale also made the tricks conspiracy-like theories use less effective. Good riddance to gatekeepers, but now we need to be more active in protecting ourselves against these ideas. We need to apply the conspiracy smell test to everything we're being told. And if that brand new idea you read in some blog fails part of the test, you might want to be careful.

Here are some of the odors I'm thinking of:

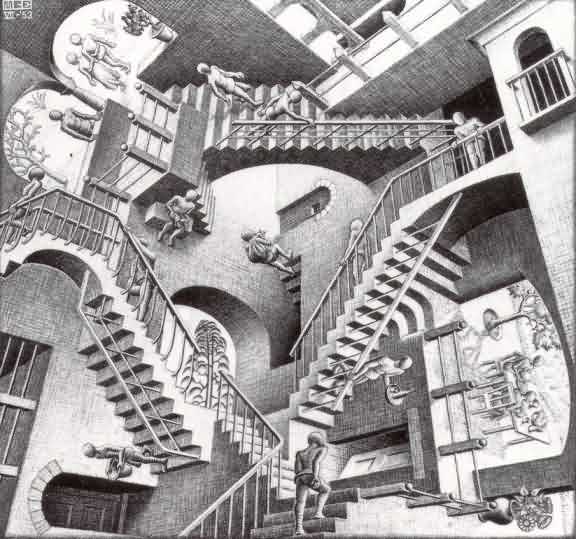

- Small, greedy ideas that force you to reinterpret a large body of knowledge. Think of the optical illusion where you can choose to see a cube from one side or the other. Or Escher's Relativity, where the building looks different depending on which staircase we choose to take as point of reference. Worldviews are a bit like that, except instead of one cube or three staircases we have millions of facts and ideas that can take on a differenct appearance depending on what our point of reference is. The small and greedy ideas I'm thinking of are like one staircase that forces you reorient ten - there might be good reason to, but as a rule of thumb there isn't.

- Small, greedy ideas that force you to reinterpret a large body of knowledge. Think of the optical illusion where you can choose to see a cube from one side or the other. Or Escher's Relativity, where the building looks different depending on which staircase we choose to take as point of reference. Worldviews are a bit like that, except instead of one cube or three staircases we have millions of facts and ideas that can take on a differenct appearance depending on what our point of reference is. The small and greedy ideas I'm thinking of are like one staircase that forces you reorient ten - there might be good reason to, but as a rule of thumb there isn't.

I'm not sure that makes any more sense than the Escher picture, but here's an extreme example: Let's say you learn that the Holocaust was massively exaggerated in order to financially benefit the Jews. In order to believe that, you must reinterpret everything that's known about post-WW2 history, about democratic governments, about societies, about historical science, about the behavior of people. Getting some new political preferences and views about genetics helps too. Once you've done that, your new worldview is internally consistent. The guy on your staircase is walking the right way, all those others guys have totally misunderstood gravity.

Reliable ideas are usually not like that, (though anything is possible.) If an historian uncovers a new aspect of Hitler's character, that may mildly affect what we know about World War 2, but affects not at all what we know about the fabric of society itself. Reliable ideas are usually humble, they affect their immediate surroundings. Beware of greedy ideas.

- Worldviews surrounded by aggressive information filters. To accomplish that Escher effect you need some way of interacting with conflicting worldviews. Some way of explaining the different orientation of other staircases. Claiming there's a conspiracy is one way to do that. "They know the truth, but they have all conspired to keep it secret." But most people are immune to conspiracy arguments. There are better way to set up a wall of information filters that will keep conflicting ideas away, more plausible arguments to use: "They say that because they're a pampered elite out of touch with the real world." "They say that because they're politically biased." "They have financial incentives." "They don't know any better, they're in the grip of a powerful fallacy." "Well that's followers of the X movement for you, they just hate everything good and decent." "I don't listen to what that person has to say, he's a known liar and fanatic."

Properly set up, and selectively applied, these filters make it possible for a worldview to coexist with massive amounts of contradictory information. Actual appeals to conspiracy are just the far end of a long scale. Aggresive information filters are less extreme but more effective. Standing on the outside, what you should ask yourself is "if they're wrong, would they ever find out?"

- Anything that's radical, new and ridiculed. You probably think I'm joking, but I'm not. A popular trick used by conspiracy-like ideas is the Galileo gambit, which can be summed up as claiming you're like Galileo just because the establishment ridicules you and your radical new idea. But history is full of radical new ideas that were ridiculed and censored .. and were dead wrong. New and radical ideas are usually wrong. And then there are those that aren't, and end up changing the world, but the point is that the odds are always against new ideas. That's the rule of thumb I mentioned above. It's boring to live by it absolutely, but reckless not to consider it at all. I don't want to you reject any idea that's completely new, just point out that that's the direction conspiracy-like ideas will be coming from.

- Focus on martyrdom and bravery in the face of the establishment. Any idea that makes its own persecution a selling point should set off alarms. Being brave has nothing to do with being right, but getting sympathy has a lot to do with convincing people.

- Bypassing the scientific and academic community and appealing directly to the public. If that brave scientist has given up trying to convince other scientists, and is writing bestsellers instead, it's possible that he does this because the establishment is too entrenched to admit the brilliance of his ideas, but more likely that he does it because professionals have better bullshit detectors than the public, and because there are more money to be made among the latter.

And then there are those signs that we might think would mark a good idea from a conspiracy-like one, but in reality don't:

- Supporters in the establishment. Every single conspiracy-like theory ever has boasted the support of people with respectable credentials. Holocaust deniers even claim support among Jews, and when that's possible, no display of token credentials should ever come as a surprise, or be taken to mean anything.

- Large quantities of supporting literature. No bad idea yet has failed to be promoted by books, and those that have been around a while will easily provide you with reading material for the rest of your life. What matters is the amount of data and research as compared to competing ideas in that field, not how long it would take you to read it all. Bad idea systems are often big. Good idea systems are bigger.

- Appeals to skepticism and awareness of logical fallacies. Skepticism is the basis of science, but it's also enlisted by conspiracy-like ideas. Just because someone recognizes the mistakes of others, that doesn't mean they recognize their own. Every conspiracy theorist will tell you they don't believe in conspiracies. Every promoter of conspiracy-like ideas will assure both themselves and you that they're not at all like those other freaks, for in their case the establishment really is afraid of their brilliant new idea. The human mind is exceptional at applying high standards to others, and liberal at making exceptions for itself.

- Having sane, friendly and intelligent followers. We'd sure like our conspiracy theorists to be insane and evil, but they're not. They usually mean well, and believe in what they do, like we all do.

- Having insane, unfriendly and stupid opponents. Jerks are everywhere, even on your side.

If you apply the smell test to your own beliefs, you'll probably find some matches. I do. That doesn't prove those ideas wrong, but it does mean we should be cautious. The stronger the smell, the more uneasy we should be. Maybe the idea itself is good or has potential that should be explored, but we've built a layer of irrational rhetorics upon it. Or maybe we've allowed ourself to become a cell of one of the many predators that stalk the idea world.

If in doubt, look to science, not logic and direct observation. Logic is great, but flawed by our inability to use it right. You can know the latin term for every fallacy there is, and still fall for all of them. Direct observation is important, but easy to misinterpret. Science is a layer built on top of logic and observation that compensates for their flaws. As annoying as this is to admit, if there is a scientific establishment consensus about something, you should probably give more weight to that than to your own logic and power of observation. Even if you think there are special circumstances, (for there always are).

And when there isn't a scientific consensus to consult, there's often a reason for that: there's no good way of knowing. That's the case with many political issues, which is why political worldviews are so often conspiracy-like. We have a strong need to form opinions, and when there's little of scientific value to base them on, we use other tools to convince us of our own good sense and righteousness. Tools perfected by conspiracy theories, generated through trial and error for one purpose alone, to make people, by any means possible, believe.

What I worry about the most is the cultism aspect of many organizations. How you, if you belong to a certain tradition or political party or scientific school, hold a deep scepticism towards "the others". Those from the opposing political party, or that other religion, or those people who do/do not believe in the evil/goodness of the World Bank, IMF, Stoltenberg, Bondevik or capitalism.

Your Escher analogy is very suitable, and to me it is clear that we must be open for the fact that our world-view is just one of several possible ones, and that neither of us can claim to have the right one.

The challenge is to find the right balance between moderation and extremism. It is easy for us to become paralyzed by our wish to see things from all kinds of perspectives; I remember my mixture of emotions on 9/11 and my lack of ability to come to any conclusions apart from the vague and potentially dangerous "We must think before we act now".

To me, to send soldiers to a foreign country to kill and be killed is pretty extreme, but sometimes it is necessary. The problem around all of this is the lack of transparency - how one uses one set of arguments publicly as the reasons for doing something, while in reality these arguments are just a small piece in a larger picture. Or maybe not.

Bjørn Stærk | 2005-10-09 15:41 | Link

Raymond Kristiansen: Your Escher analogy is very suitable, and to me it is clear that we must be open for the fact that our world-view is just one of several possible ones, and that neither of us can claim to have the right one.

Well, we can. There's only one reality, and whatever views that don't conform to it are either wrong or deal with the unknowable. The hard part is knowing whether you've found the right one. The lesson of Escher's staircases isn't that there are more than one correct way of looking at the world, but that there are many that seem correct, and that it's not enough to demand of worldview that it's internally consistent and knows how to deal with the competitors. Any view can do that.

Instead we need to build on something that goes beyond specific worldviews, a method that isn't easily fooled by tricks. And that's science, (decentralized, networked thinking and experimentation). It also helps to be aware of how these worldviews operate, how they work to make us believe them.

It's also possible to take a completely theoretical approach to this and spend much time thinking about how we can really know anything, and how we can really prove that what we know is true. But in daily life it's more important to just have a few rules of thumb that help us detect bad ideas when we come across them. Finding the Big Truth is an intractable job, that's why good heuristics (like science) are more of use to us. (In fact, bad ideas find it easier to exploit promises of Big Truth than to exploit science .. anything can be made to seem perfectly Logical and Absolutely True, making testable predictions is much harder.)

H.sorensen | 2005-10-09 23:51 | Link

Tough one to separate truth from false, I would say that just knowing that there is alot to question is a good start. I used to believe in almost anything but along the way I have learned a thing or two.

1. If I know almost nothing about a subject,I check out arguments on both sides.

2. if the idea support to much fancy talk like "quantum, Perpetuum mobile,.." and it comes from someone without a nobel prize, be cautious.

3. Occams razor: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam's_razor . Given two equally predictive theories, choose the simpler.This isnt always true but it is a beginning.

4. www.randi.org and http://www.noah.org/science/reason.html will do "wonders" to fight superstition

"Modern" conspiracy theories like Bush was behind 911 and that the Iraq invasion was all about oil can be hard to discredit it takes time and effort and most of all knowledge. Thats why so many people believe in them I guess. A good Conspiracy will always hold some truth, and honest well meaning people will believe in them and support it.

I somtimes think that people actually is willing to believe in almost anything as long as it isnt true.

Jeff Dege | 2005-10-10 18:29 | Link

Charles MacKay's "Extraordinary Popular Delusions & the Madness of Crowds" was first published in 1841.

Allan, Singapore | 2005-10-11 04:05 | Link

H.Sørensen:

"3. Occams razor: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam's_razor . Given two equally predictive theories, choose the simpler.This isnt always true but it is a beginning."

Oh, I agree. And it applies especially on this subject:

"Modern" conspiracy theories like Bush was behind 911 and that the Iraq invasion was all about oil can be hard to discredit it takes time and effort and most of all knowledge. Thats why so many people believe in them I guess."

Now, is it more realistic to think he did it because first: Saddam was making WMD's, oh no, he was not making.. just in the process of making.. oh no, he 'had the intention of making WMD's'. Ah, heck.. he was evil, we had to free Iraq!

OR

We did it to secure a stable oil supply.

Heh, I guess the most simple explanation wins this time also. :p

Erik Naggum, Oslo | 2005-10-12 10:56 | Link

Regarding logic. It's worst problem is not that we do not use it right, but that it is so much easier to work our way from false premises to logically sound conclusions than from true premises to new truth. The human mind is much more productive in inventing than it is in observing the external world, so if you already know where you're going, you can just use good logic in reverse until you have built a solid foundation for your castle in the air. That's how conspiracies get going in the first place: They sound reasonable given the premises they are built on, and are often much more logical than science and reality is. Logic is a necessary, but far from a sufficient element in any good theory -- which is also why testing hypotheses is increasingly expensive: The truth we need to uncover to move science further is harder and harder to get at, and finding new true facts as premises that affect our understanding is consuming vast amounts of brain power, huge research budgets, and enormously conplex instruments. Using logic in reverse from their armchair philosophizing position is now the only chance most people have to arrive at new things to believe in. So I contend that it is not the misuse of logic that is the problem, but rather that it is used exceedingly well by those who believe that making stuff up and then rationalizing it with reverse logic will move them closer to the truth. The pervasive requirement to be logical in our society has made for much better fiction and much more believable alternative realities, however. So curiously, the requirements of science has made for much better conspiracy theories -- illogical flights of fancy never make it in our world.

K E Ellingsen, Skien | 2005-10-12 20:48 | Link

You're diving quite deep into a core value of scientific philosophy here, Bjørn. Too bad it took only 3 posts before a traditional US foreign policy debate was spawned, but in this you should blame yourself- most of those visiting your site is vividly interested in US (foreign) politics.

What you are driving at has, among a myriad of other places, been summed up by Terry Pratchett - the idea of someone being substitious (as opposed to superstitious)- that is they believe in what really is instead of what everything seems to be. (This was ascribed to one of the main characters in "Jingo", a Discworld novel. It is a enjoyable read by the way).

KEE

Andrew X | 2005-10-23 23:18 | Link

"Now, is it more realistic to think he did it because first: Saddam was making WMD's, oh no, he was not making.. just in the process of making.. oh no, he 'had the intention of making WMD's'. Ah, heck.. he was evil, we had to free Iraq!"

SIGH

Isn't this the same simplistic BS that this entire post has been talking about? How about the other reasons Bush gave, such as appalling human rights violations, AND virtual mockery of the UN resolutions, AND no less than three unprovoked attacks on neighbors for the sheer purpose of rapine, loot, annexation and/or vengeance, AND forthright support of terrorism in the Middle East and beyond, AND the actual use of WMD against Iran and his own people, AND being an iron foundation of virtually every economic, political, and spiritual failing in the region for forty years, namely rabid, psychopathic, personality cult one-man rule, to an extent that no European King or Queen EVER came close to matching in all history. Only Leftist dictators like Stalin, Mao, Kim & his kid, Ceacescu, and yes Hitler, that National SOCIALIST, and Saddam with his Baathist socialist party (a party inspired by and even set up with the assistance of Nazi Abwehr boys during the war to oppose the British there) can meet that level of absolutism.

Of course, how could we know that when Bush made his case, citing ALL of the above (except the very last point) and more, in secret? After all, the only people he told it to were, um, the entire United Nations General Assembly and everyone in the hall at the time. I mean, who watches THAT??

Fact is, the idea that the Iraq conflict was "all about WMD" is in fact itself a lie, the kind of which is the very point of this discussion.

You want a simple reason for the war? How about... because no two democracies have EVER, repeat EVER, gone to war. Got an exception? Let's hear it.

Thus, replacing tyranny with democratic rule in which citizens have an actual stake in their societies results in a more peaceful region over the long run. Dare I mention Kosovo? Remember Yugoslavia in the 90's? Remember the headlines? Remember the last headline you saw from (former)Yugoslavia?

Uh huh.

Meanwhile, one-man tyrannies are a repeated and unceasing source of endless and eternal war, and will be tormorrow, next year, and next decade, and so on, as long as they exist.

Millions, nay BILLIONS, of people want to see an end to war. No two democracies have ever gone to war. Got anything simpler than that? Let's hear it.

Yet the Left marches for and loves their one-man tyrants, their Mao's, and Castro's and Saddam's and Mugabe's...and always will. Got an explanation for THAT? I sure don't. I'll take that mystery to the grave.

Sensi, Paris | 2005-10-28 09:46 | Link

«the idea that the Iraq conflict was "all about WMD" is in fact itself a lie»

The USA government claim to go to war in Iraq while it was in front of the U.N. was only on that specific topic, please don't pratice revisionnism, that is only ridiculous.

«Thus, replacing tyranny with democratic rule in which citizens have an actual stake in their societies results in a more peaceful region over the long run.»

Well, i will remember you that Saddam Hussein was put in place by USA's CIA. That's a fact: Iraqi people have only endured CIA's dictator for decades, an american choice 'over the long run'.

I am pleased that CIA's dictator have benn removed, but now that they have given power to confessional milices all this under the law of charia, Iraqi people will soon be grateful, doubly.

cf. http://www.upi.com/inc/view.php?StoryID=20030410-070214-6557r

To speak of democracy when the last try of an extreme-right coup d'etat from USA's CIA was in 2002, against the democratically elected Chavez, that's funny and believable (sic).

Best regards,

Sensi

Sensi, Paris | 2005-10-28 10:30 | Link

«Yet the Left marches for and loves their one-man tyrants.»

Of course, brave right-wing americans are far more humanists when they request, marches for and loves their extreme-right tyrants put in place by their patriotic CIA to 'secure' their interests...

http://www.serendipity.li/cia/cia_time.htm

http://www.serendipity.li/cia.html

(first google result, seems at least reliable for summarizing the content)

Best regards,

Sensi

n.b: i am btw a moderate-right conservative and not an horrible 'lefty'. Thus you will be short on this, biased, 'partisan opinion' argument.

Stein, Oslo | 2005-10-31 06:22 | Link

Democracies and war

Andrew challenges people to list examples of (liberal) democracies that go to war with *each other*.

That's a red herring.

Maybe a more relevant question would be "does democracies sometime start wars that are hard to justify - ie wars where the democracy might justifiably be termed the aggressor nation ?".

Iraq is a prime example of this. No matter how you twist and turn, the United States of America, which is a democracy, did initiate that war.

Grin,

Stein

anton, holland | 2005-10-31 09:53 | Link

This "Clash of the Theories" is a particular form of paradign shift in science as described by Thomas Kuhn. I am glad to read here some interesting observations on validity and the role of logic, and who the supporters are. Nice.

Sigve Indregard, Oslo | 2005-11-29 12:03 | Link

Right or wrong world view? I agree with Stærk in principle: There is only one (actual) reality, although we could envision multiple realities. I prefer to view these realities - also the actual one - as a collection of events.

It is nevertheless correct that this reality has several equally correct descriptions, each of which presents the happenings differently (in a different perspective, in a different light). Such descriptions may all be factually correct, but still present different "world views".

So, when the socialist claims that the capitalists "conspire" to keep the working class poor, it may not be directly recognizable under the capitalist description, yet are the facts probably correct. The same goes the other way around, when the capitalists claim that labour unions are hampering productivity and competitiveness. Both these descriptions are in a way correct, and most descriptions of power are of such nature.

Power structures are doomed to be described in simplified ways ("the capitalists keep us poor"), because the more elaborate explanations are much longer and give generally the same result ("the structure of the economy is such that every owner of a factory will try to maximize..."). It is this sloppiness, this unprecisity, which opens the space for conspiracy theories. They feast on such sloppy descriptions to build a world where the capitalists or labour union leaders actually come together to conspire. Then, add a UFO.

We can very well speak of more or less correct world views, but for all practical uses we can hardly present a single correct one. We are almost always forced to admit some space for doubt because of the unreliability of our knowledge and senses. Your smell test will always work better on other people's arguments than your own. It is a test of how far from your own world view the argument is, so you won't smell your own world.

Sigve Indregard, Oslo | 2005-11-29 12:09 | Link

Correcting my end point in the last comment: The smell test is a test of how far from your world view the argument is, not of how far from the actual (and factual) world the argument is. You won't smell your own, but that does not by law make your world any closer to the actual world.

I'm on your side, though, when you elaborate on how you "find your way" in your own world view: I do also believe that there are ways to find facts, and that the academic society generally is best at it. But history is crowded with academics who build very strong worlds of non-facts, to create epicyclic knowledge. We need to remember that, or our arrogance will fool us.

Trackback URL: /cgi-bin/mt/mt-tb.cgi/1698

SEIXON: The Truth Is Never Enough, October 13, 2005 07:30 PM

The anti-war movement creates yet another conspiracy theory about the war in Iraq and the coalition. Increasingly these theories are ushered into existence by disinformation campaigns carried out by our true enemies. In this example, the al-Sadr moveme...

Comments on posts from the old Movable Type blog has been disabled.

Sigve Indregard, Oslo 29/11

Sigve Indregard, Oslo 29/11

anton, holland 31/10

Stein, Oslo 31/10

Sensi, Paris 28/10

Sensi, Paris 28/10

Andrew X 23/10

K E Ellingsen, Skien 12/10

Erik Naggum, Oslo 12/10

Allan, Singapore 11/10

Jeff Dege 10/10

H.sorensen 09/10

Bjørn Stærk 09/10

Raymond Kristiansen, Bergen 09/10