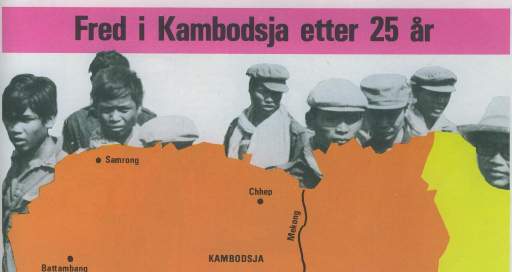

Kambodsja gjennomgikk 25 års fødselsveer

Det gamle kongeriket Kambodsja fikk gjennomgå 25 års fødselsveer før den egentlige oppbyggingen av landet i det hele tatt kunne påbegynnes.

1949. Kongedømmet Kambodsja ble en selvstendig stat innenfor den franske unionen.

1953. De pågående kampene mellom franskmenn og vietnamesere spredte seg inn i Kambodsja. Kambodsjansk gerilja begynte å delta i frigjøringskrigen mot franskmennene.

1954. Genève-konferansen satte stopp for krigen i Indo-Kina. Kampene avtok og franskmennene trakk seg tilbake.

1955. Kambodsja ble helt selvstendig. Kong Norodom Sihanouk frasa seg tittelen, men beholdt posten som statssjef. [..]

1969. General Lon Nol ble utnevnt til statsminister med vidtgående fullmakter.

1970. Fyrst Sihanouk ble styrtet ved et militærkupp ledet av Lon Nol. Statsministeren proklamerte republikk og utnevnte seg selv til marskalk. Sihanouk flyktet til Peking. USAs daværende president Richard Nixon tillot amerikanske og sør-vietnamesiske styrker å invadere Kambodsja i sin kamp mot FNL. I Peking dannet Sihanouk eksilregjeringen GRUNK.

1971. Den nasjonal frigjøringsfronten FUNK hadde stor fremgang og kontrollerte snart den største delen av landet.

1973. USAs mest intense bombing av Indo-Kina ble innledet mot FUNK-geriljaen. I august ble bombingen stanset av den amerikanske kongressen. I Kambodsja proklamerte Lon Nol unntakstilstand.

1974. FUNK rykket inn i den tidligere kambodsjanske hovedstaden Gudong. Byen ble imidlertid gjenerobret av regjeringsstyrkene, men da geriljaen innledet en kraftig offensiv ved årsskiftet, ble Lon Nol-regjeringen tvunget til å overgi den ene viktige stillingen etter den andre. USAs president Gerald Ford krevde ytterligere bevilgninger til Lon Nol-regimet, men fikk avslag av kongressen. Dermed var også geriljaens seier et faktum.

- Det hendte 75

Louis B. Mayer (1884 – 1957) was

Louis B. Mayer (1884 – 1957) was